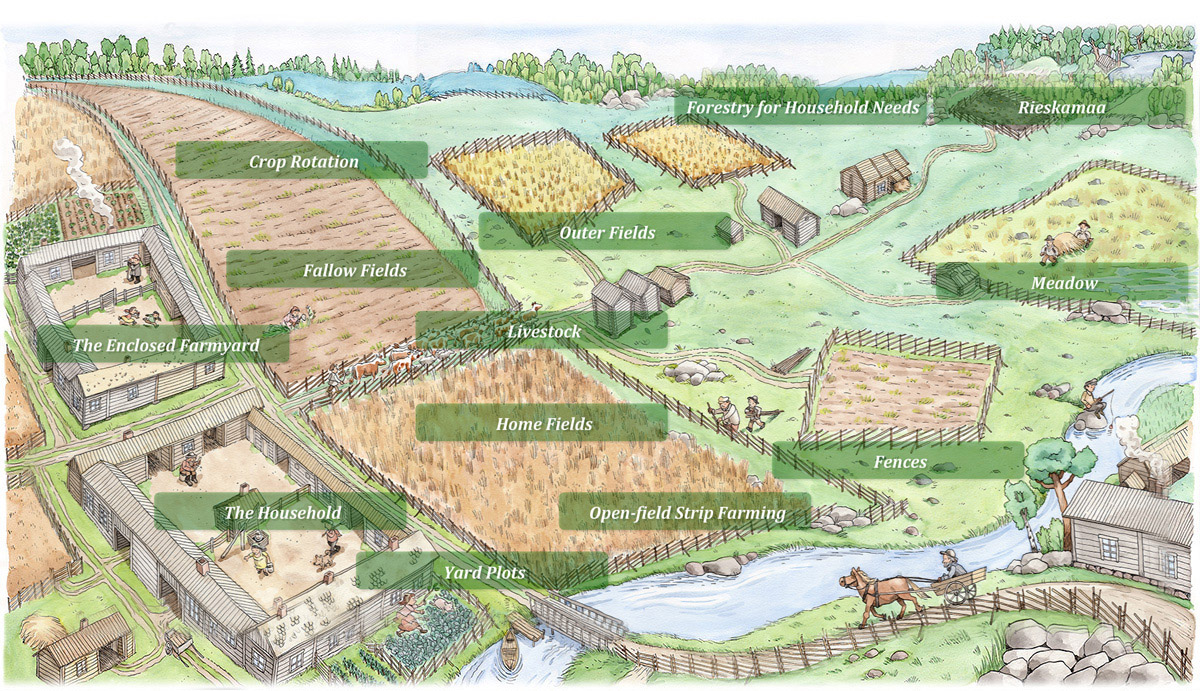

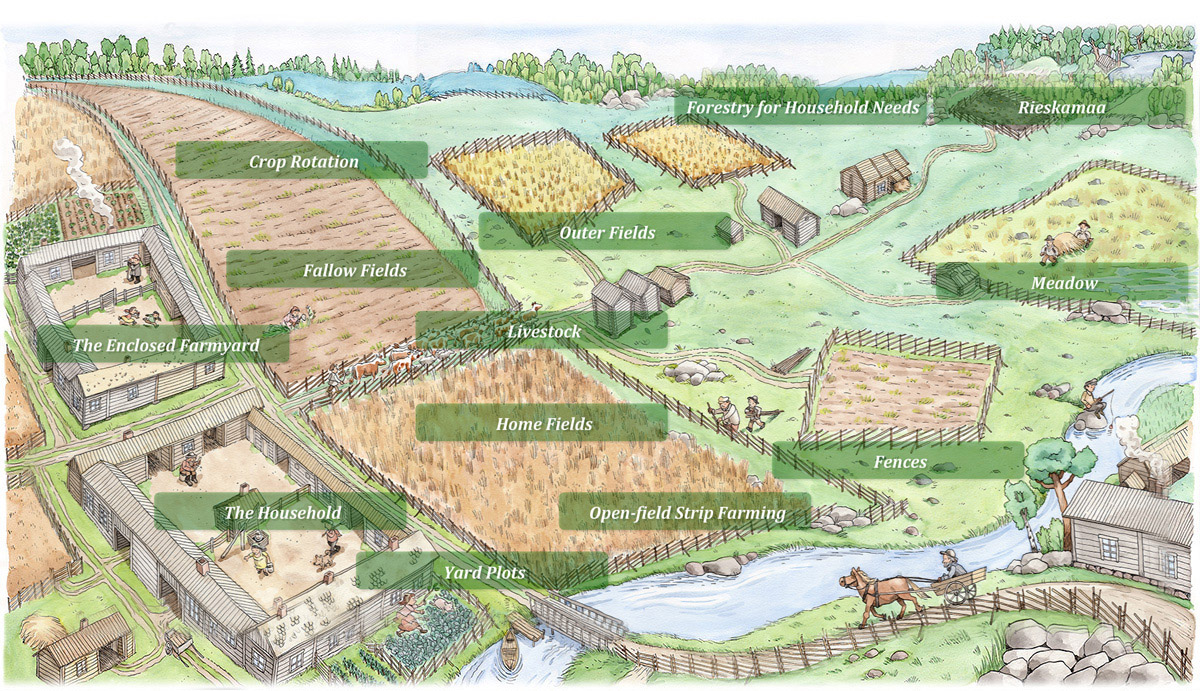

There were various systems of crop rotation in arable farming:

The one-crop system. The same crop is grown in the field from one year to another without a fallow stage in between. Monoculture requires considerable fertilization and it was mainly applied in small fields and in barley cultivation in Northern Finland.

South-Finnish two-shift rotation. The main cycle of this crop rotation was between growing rye and the fallow stage, with one half of the field under cultivation and the other half left fallow. Alongside the main rotation there were additional cycle for growing, for example, barley, root crops, peas or flax.

North-Finnish two-shift rotation. Also in this form of two-shift rotation, half of the field was cultivated while the other half lay fallow. The rotation actually involved four stages: fallow – rye – fallow – barley. This meant that the same grain species was grown every fourth year in the same section of the field.

Three-shift rotation. In three-shift rotation, the stages were fallow, winter grain (rye) and spring grain (barley). This system provided more efficient utilization of the fields than two-shift rotation, since only a third of the field lay fallow. It required good fertilization as the field was fertilized on the same occasion for two species of grain and two harvests.

×

Leaving fields fallow was an integral part of traditional arable farming. In turn, there would always fallow uncultivated fields of a farm. Despite this, a fallow field required work, for it was ploughed several times during the summer. The fallow stage was regarded as important for preserving growth especially when fields could not be fertilized well because of insufficient manure. Of greater importance, however, was the fact that the fallow stage helped control the growth of weeds. Two-shift rotation in which half of the field was planted and half lay fallow was the most common method of cultivation in the 18th century. Before being ploughed in the summer, the fallow field often served as pasture for livestock.

×

In the arable farming area of the Finland, farms were usually close to each other on densely built village sites or tofts. The enclosed farmyard was the most typical yard area. It was surrounded by the dwelling house, storehouses, sheds for storage, firewood, carriages and sledges and for sleeping in the summer, along with a stable, a cow barn and fodder stores. The yard was divided with a fence or buildings into a dwelling area and a yard for livestock and animals. The threshing shed and the sauna, which could easily cause a fire, were usually located outside the close group of buildings. The granaries were often located separately to avoid the grain from being destroyed in case of fire.

×

In Western Finland average family size was smaller than in the eastern part of the country. The household would consist of the farm owner couple and their children and possibly unmarried siblings of the husband or wife. Depending the family’s situation, there would also be hired maids and farmhands. Hired help was needed more when the family’s children were small, and less when the children grew to take part in work on the farm. Working as hired help was a typical stage of life before marrying, after which a couple would go on to set up their own household.

×

Small fields were located close to the village site, or toft. They were small cultivated plots that were not left fallow at all and were instead fertilized to a great deal to maintain growth. They were used to grow plants and vegetables that were needed only in small quantities, such as cabbage, turnips, flax and hemp. When potatoes were introduced, they too began to be grown in these small plots. The plots were often named according to the plants or crops grown there, being called, for example, a cabbage patch.

×

Most of the farmed area consisted of the so-called home fields around the farmhouse and these fields are usually implied when speaking of arable farming. The home fields were often divided into two fenced sections, since two-shift rotation was the most common method of cultivation. The sections alternated between growing grain and lying fallow. The sections were in turn divided into strips cultivated by the individual farms of the village. The most common grain species in the home fields was rye. Barley was also grown. Part of the field lying fallow could be set apart for cultivating peas, beans, root crops, flax, hemp or barley. Various forms of two-shift rotation evolved, and in the late 18th century three-shift rotation (fallow, winter grain, spring grain) gradually began.

×

The numbers and care of livestock mostly depended on the availability of fodder and the need for manure. Livestock was mainly needed to provide manure for the fields, but meadows in natural condition rarely produced enough fodder for feeding the animals in winter. The largest numbers of livestock were in the coastal areas of Ostrobothnia in Western Finland, where fodder was most readily available. In most parts of the country, livestock had to be fed with secondary fodder.

Horses were given hay and oats, because they had to remain in good condition for hauling and transport in the winter. The best wool from sheep was sheared in winter, and it was not worthwhile to let their condition deteriorate. They were mainly fed dried leafy branches. If there was hay for cattle, it was given only to cows that were pregnant or had calved. Cattle mainly ate straw and were also given feed made of threshing remains, cut straw, pea steam, the tops of root crops, leafy branches, hay and finely chopped conifer branches steeped in hot water. Pigs fared the worst, having to look for their own food most of the year.

During the summer livestock foraged in the forests, fields that lay fallow and in meadows after the hay had been cut. In the region of arable farming, pastures were often small and of poor quality.

×

So-called outer fields were usually small fields cleared near the village. They were less valuable than the home fields and they were often poorly fertilized. Secondary crops such as oats for animal fodder were grown in them. The cultivation techniques of these fields could also differ from those of the home fields. As settlement and farmed areas expanded, the outer fields were joined to the home fields, but new ones were also cleared.

×

The shared field of the village was divided into regular strips among the farms of the village in accordance with the taxation of individual farm properties. A farm with the highest tax burden would be given the largest area to cultivate. The division was carried out in the same way as hay or catches of fish were distributed. The total amount did not have to be known when everyone was given their share according to a set measure. The field was measured with a special rod starting from one end. A strip was consecutively measured for each farm. The width of the strip was the number of rod lengths that corresponded to the taxes payable by the farm in question. The strip extended in the same width from one end of the field to the other. When each farm had been given its strip, the round started again from the first farm and the process continued all the way to the end of the field. The distribution of land was rarely complete, and the part remaining at the end of the field area was often measured into crosswise strips. As a result, each farm had dozens of strips in the fields around the village. Owing to the technique of dividing land, each property was given its share of both good and poor farmland.

×

Forests were not yet of any monetary value in the 18th century. Timber was sold in small amounts and its price consisted of related labour and transport costs. On the other hand, wood was used to a great deal in households, mostly as firewood for heat and light. Timber was also used for construction. There were many buildings on farms since it was customary to build all outdoor storages spaces separately. In addition, wooden buildings without stone foundations did not last long, and thirdly wood was needed for fences and for making tools, sleighs, carriages, furniture and household vessels..

×

Slash and burn methods were also applied in the region of arable farming. As settlement densified, increasingly smaller areas of forest remained for slash-and-burn farming, and by the 18th century there were few opportunities for practising it on a large scale in Western Finland.

A slash-and-burn plot in young deciduous forest was known in Finnish as rieskamaa. The trees were felled when the leaves sprouted and were burned in the same spring. A plot of this kind could be cleared only on sunlit slopes that would dry quickly. After burning over, the plot was usually planted with turnips, but also barley, buckwheat and flax were grown. The rieskamaa plots would provide two crops, but the same plants were not grown in consecutive years. After the second crop, the site became a meadow or was left to be overgrown with forest again.

×

According to an old Finnish saying, the meadow is the mother of the field. Livestock were needed to fertilize fields and fodder for cattle was gathered from meadows. The larger the meadows of a village were, the more livestock could be kept with in turn more fertilizer for the fields. The common meadows of the village were divided into strips like the fields or the jointly harvested hay was shared among the farms. The hay from meadows further away was stored in barns or stacks.

New meadows would be cleared they were tended to only a small degree. They were mainly prevented from being overgrown by forest or from forming hummocks.

×

Fences were a dominant element in the rural village landscape of the 18th century. The fields and meadows near the village were surrounded by strong fences to prevent freely grazing livestock from damaging the grain or hay crop. Crop rotation could change the function of fences according to the season and year. The fence of a field under cultivation kept livestock out of it, while a field lying fallow could be used as pasture and the fence kept the animals inside. While fences were mostly made of spruce, the preferred material was aspen. It was said in Jämsä in Central Finland that the strongest things in the world are a pole of juniper, withes made of spruce and fence posts and spars of aspen.

Fences were required by law. Each farm had to participate in building the joint fences of the village in accordance with shares of fields and meadows. Neglecting the duty to enclose fields led to fines and the obligation to pay compensation for loss or damage caused by poorly built fences. Fields and meadows had to be kept enclosed until they were harvested.

×