In the Eastern Finland, families were on the average larger than in Western Finland. Several brothers with their spouses and children could live in the same household. It was only after the death of the old owner that the property was passed on, with the brothers either continuing to live together or moving on to set up their own households. Family relations on the father’s side were of great importance, and therefore women had a weaker position within the family. Women married at an early age into the households of their husbands to give birth to children and to work.

Farms in Eastern Finland had few hired hands or servants, because the extended families provided labour of their own accord. On the other hand, landless persons and their families would live on the farms along with the owner family. Additional labour for slash-and-burn cultivation could be arranged by establishing joint burn-clearing ventures. In the late 18th century, farm households started to become smaller as growing numbers of landless people began to establish their own households.

×

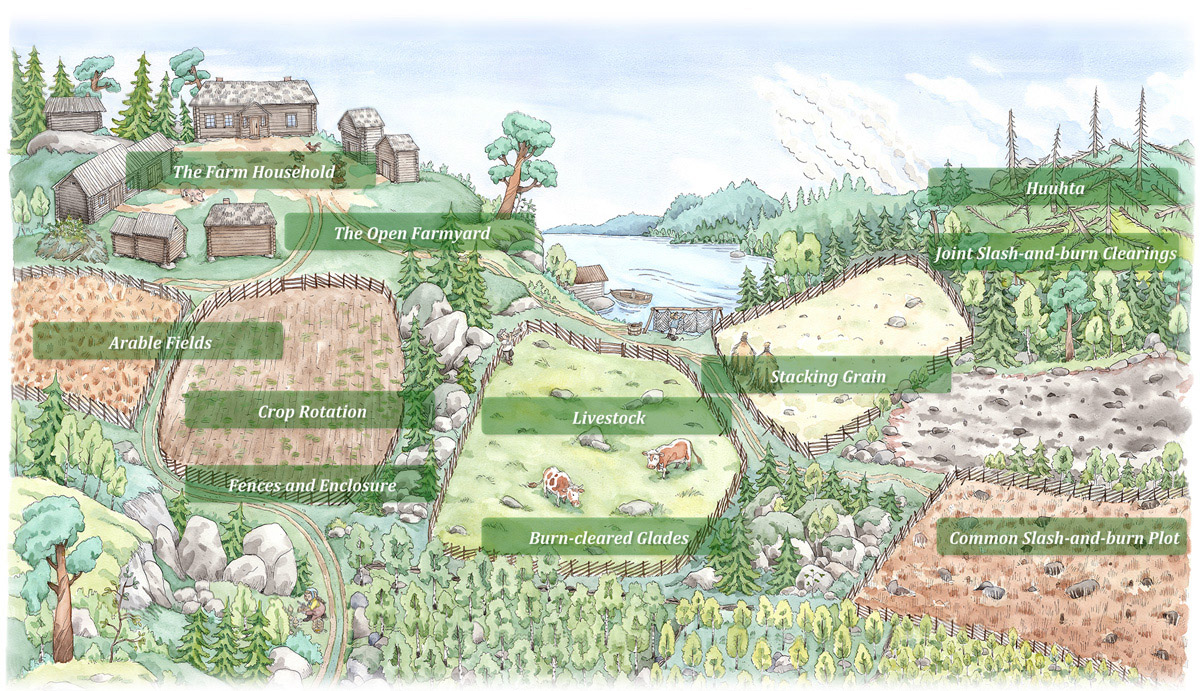

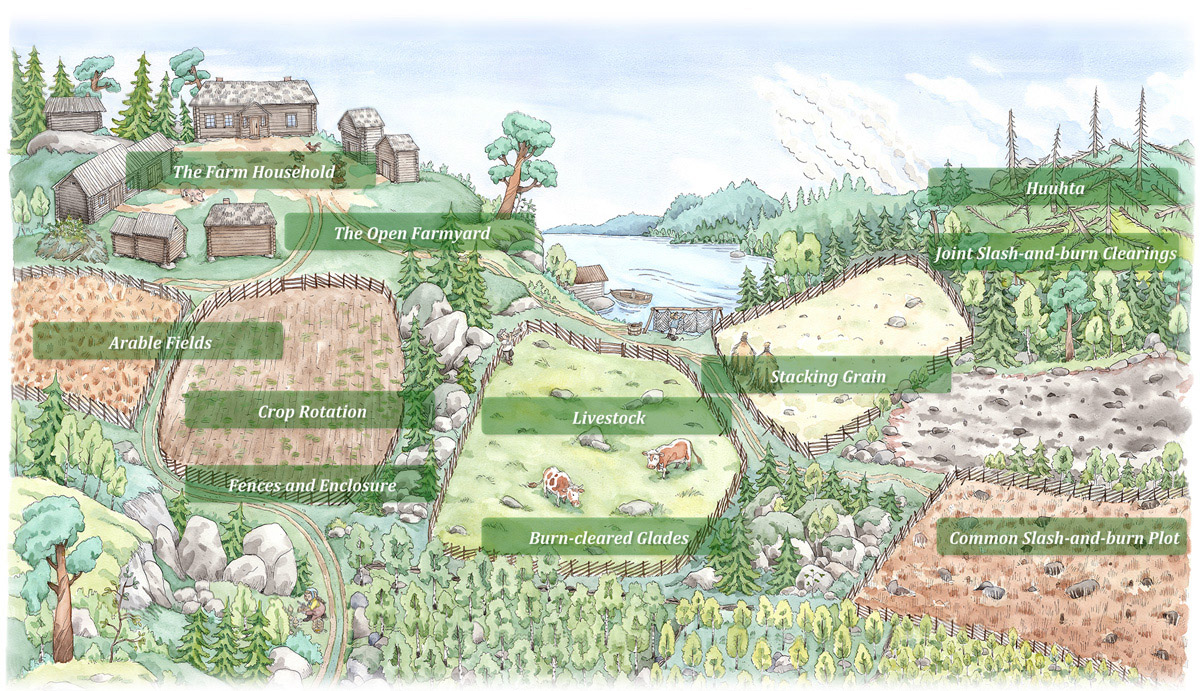

In the regions of slash-and-burn farming, the yard areas of farms were usually located separately on the slopes of hills. The most common type was the open yard, where the locations of the buildings were dictated by the terrain and practical considerations. The number of buildings and structures in a farmyard could range from a few to as many as twenty. The movement of cattle was directed by fences and special areas were fenced for them. The dwelling house was at a higher elevation than the other buildings, and the cow barn was built close to the well. Other important buildings in the yard were the stable, storehouses and sheds for sleeping in the summer, the threshing shed, the sauna, storehouses for fodder, and sheds for firewood and sledges and carriages. There were often many small sheds built separately for the adult members of the household and the families of siblings where they could sleep in the summer months

×

Also in the slash-and-burn region some crops were grown in fields located near the farmhouses. They were clearly smaller than in the areas of arable cultivation, and the fields of each farm were separately fenced. Both two-shift and three-shift crop rotation were followed in the slash-and-burn region. In Eastern Finland it was customary to sow fields more sparsely than in the western parts of the country, using slightly over half the amount of seed per hectare compared with sowing practices in Western Finland.

×

There were various systems of crop rotation in arable farming:

The one-crop system.The same crop is grown in the field from one year to another without a fallow stage in between. Monoculture requires considerable fertilization and it was mainly applied in small fields and in barley cultivation in Northern Finland.

South-Finnish two-shift rotation. The main cycle of this crop rotation was between growing rye and the fallow stage, with one half of the field under cultivation and the other half left fallow. Alongside the main rotation there were additional cycle for growing, for example, barley, root crops, peas or flax.

North-Finnish two-shift rotation. Also in this form of two-shift rotation, half of the field was cultivated while the other half lay fallow. The rotation actually involved four stages: fallow – rye – fallow – barley. This meant that the same grain species was grown every fourth year in the same section of the field.

Three-shift rotation. In three-shift rotation, the stages were fallow, winter grain (rye) and spring grain (barley). This system provided more efficient utilization of the fields than two-shift rotation, since only a third of the field lay fallow. It required good fertilization as the field was fertilized on the same occasion for two species of grain and two harvests.

Fences were an important element of the rural landscape. In the regions of slash-and-burn cultivation, burn-cleared sites and fields near villages or farms were fenced in. Fences could be owned jointly or by individual farms and they were made to control cattle and animals of the forest. A fence kept animals outside burn-cleared land that was under cultivation, but when the site was no longer farmed it could be converted to pasture, and the same fence kept cattle from straying.

The obligation to enclose farmland with fences was laid down in law. Failure to do so would lead to fines and payment of compensation if damage resulted from poor fences. The fenced areas were to be kept enclosed until they were harvested.

×

The slash-and-burn areas had the smallest numbers of livestock per capita in the whole country. Cattle and sheep, in particular, were fewer than in the rest of Finland. While the small fields did not require much manure, the most likely reason for small numbers of livestock was the difficulty of obtaining fodder. Cutting hay in burn-cleared glades.was difficult because of the rocky terrain, and therefore they were used more as pasture. Only a small number of livestock could be kept over winter, while in the summer months their productivity was high owing to good pastures. The small stocks of sheep in East Finland has been explained by the risk posed by predators.

×

After the grain crops were harvested, the burn cleared site was left as a glade growing hay, where forest would grow back over time. Since there were few meadows in the slash-and-burn region, the glades were important for feeding livestock and hay could be collected from them for winter fodder. In most cases they were so stony that were they left as summer pasture for livestock. It was typical for the slash-and-burn region that its small numbers of cattle produced large amounts of milk in the summer because of good summer feeding conditions, while in the winter they suffered from limited fodder.

×

Stacks were a widespread way of storing grain grown on burn-cleared land. The stack was a round pile of sheaves of grain first widening upward and then tapering towards the top with a so-called cap sheaf placed uppermost. Stacks were made at slash-and-burn sites because they were far from the farmhouse and the grain could not be immediately brought in to be threshed. This was usually not done until winter when sleighs could be used. Some of the grain in stacks was lost to mice, birds and damage by rain, but grain could be stored in this way for over a year. Stacks older than a year became a kind of symbol of affluence, as farmers known as "kings of the huuhta [burn-cleared plots in spruce forest]" who achieved excellent yields had grain to spare for stacks left standing for longer than a year.

×

Slash-and-burn clearings known in Finnish as huuhta were made in spruce-dominated forest that had preferably not been burnt over previously. According to an old slash-and-burn farmer from Kuhmo in East Finland, spruce “burns best with a lot of ash, and ash is the manure in the huuhta”. At a huuhta site, the trees were felled and the clearing was left to dry for a year or two after which it was burned over and planted. These sites usually provided only one crop. In the 18th century it became customary to burn over the huuhta after the first crop to obtain a second one. A special feature of the huuhtas was that only a special so-called wilderness strain of rye thrived in them. It had a very high yield, and several stalks could grow from a single seed. When successful, a burn-cleared field of this kind could produce very large harvests, but it could also fail completely under unfavourable weather conditions. A rainy summer could postpone the burning of the site to be too late, or prevent it completely. Long periods of fair weather also led to failure, because the seeds would not sprout in dry burnt soil.

×

Farmers pooled resources into ventures for the felling and cultivation of large burn-cleared sites. A joint clearing was managed by several farms on land that was either shared or owned by one of the partners. Relatives were of importance when establishing these ventures, but also persons from outside the family were commonly involved.

The joint clearing ventures were not always between the owners of the farms; landless persons could also be invited to join. A partner would receive as payment an agreed share of the yield of the burn-cleared site. This provided labour for felling and burning timber, while wages did not have to paid as in the case of employees hired for a year at a time.

×

The common slash-and-burn plot was cleared in deciduous or predominantly deciduous mixed forest. A forest of birch and alder 15 to 30 years old was regarded as the best for this purpose. The trees were cut down while they still had leaves, preferably in the late summer. The felled area was left to dry until the next years, when it was burnt over and planted. Rye was mostly sown, and for this reason the site was burnt over in June or July. The burn-cleared plot was provided one crop of rye, after which oats were usually sown. One to four crops of oats were grown before the plot was left as a glade.

A slash-and-burn plot of the common type could again be cleared in the same place some 20 to 40 years later. This was a system of rotation involving a stage of clearing, cultivation and regeneration of forest.

×